Was prehistoric art inspired by altered states of consciousness?

27. 05. 2020

27. 05. 2020

Many prehistoric cultures have left behind breathtaking works of art, many of which have entered history textbooks. Looking at the murals in the Turkish Neolithic settlement of Çatalhöyük, the richly decorated vessels of the Cucuteni-Trypilja culture or the engravings in the Irish megalithic tomb of New Grange, we must ask where these motifs came from and how some of them may be repeated so often. Was it only human abstraction that conjured these ornaments, or is there something more behind it?

Portal to the realm of ancestors

Each of us experiences altered states of consciousness almost daily, for example, when we have dreams during sleep. However, profound changes in consciousness can also be brought on intentionally, for example by rhythmic drumming, dancing, fasting, isolation, sensory deprivation or psychotropic substances. Many of these techniques are a common part of the rituals of natural nations and most likely prehistoric cultures.

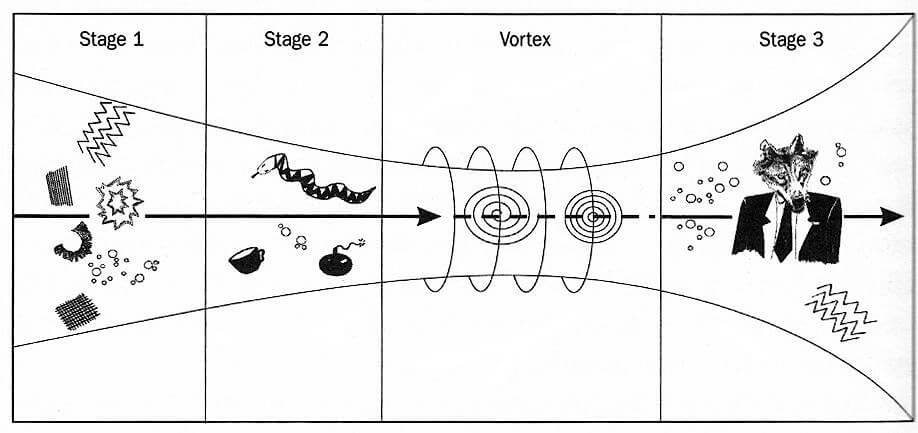

Diagram of the change of state of consciousness showing the entoptic phenomena that accompany the individual phases.

A closer look at the various manifestations of altered states of consciousness such as hypnagogy (a state between sleep and wakefulness), near-death experience, sensory deprivation or psychedelic intoxication can divide the course and intensity of these states into three phases according to so-called entoptic phenomena. In the first phase, geometric shapes such as wavy lines and chessboards appear. The next phase is a typical feeling of spiral movement or directly a vision of rotating spirals, the so-called vortex. Behind him is a world of full-fledged hallucinations and visions brimming with dream creatures and feelings of hovering or flying.

It is then clear that these experiences are reflected in the stories, mythologies, cosmologies, but also the everyday life and art of people for whom rituals evoking entoptic phenomena are common and have experienced them themselves or know them at least indirectly from shamans and medicine men. In today's natural peoples, it is possible to study these ceremonies and the connections between visions and art in living culture and to ask questions to people who have had these experiences and know their meaning. Of course, this possibility is not available in prehistoric, long-extinct cultures, and therefore the question must be asked: is it possible to find parallels between art influenced by altered states of consciousness and prehistoric art?

Prehistoric art or prehistoric visions?

Evidence of prehistoric art dates back to the early Stone Age and manifests itself, for example, in the form of statues of animals and people from mammoths, engraved art on the bones and most colorfully in cave art. It was precisely the cave art that had the deepest spiritual charge and reflected the important rituals performed in the flickering light of the good inside of the earth.

The lion's man from Hohlenstein-Stadel in Germany.

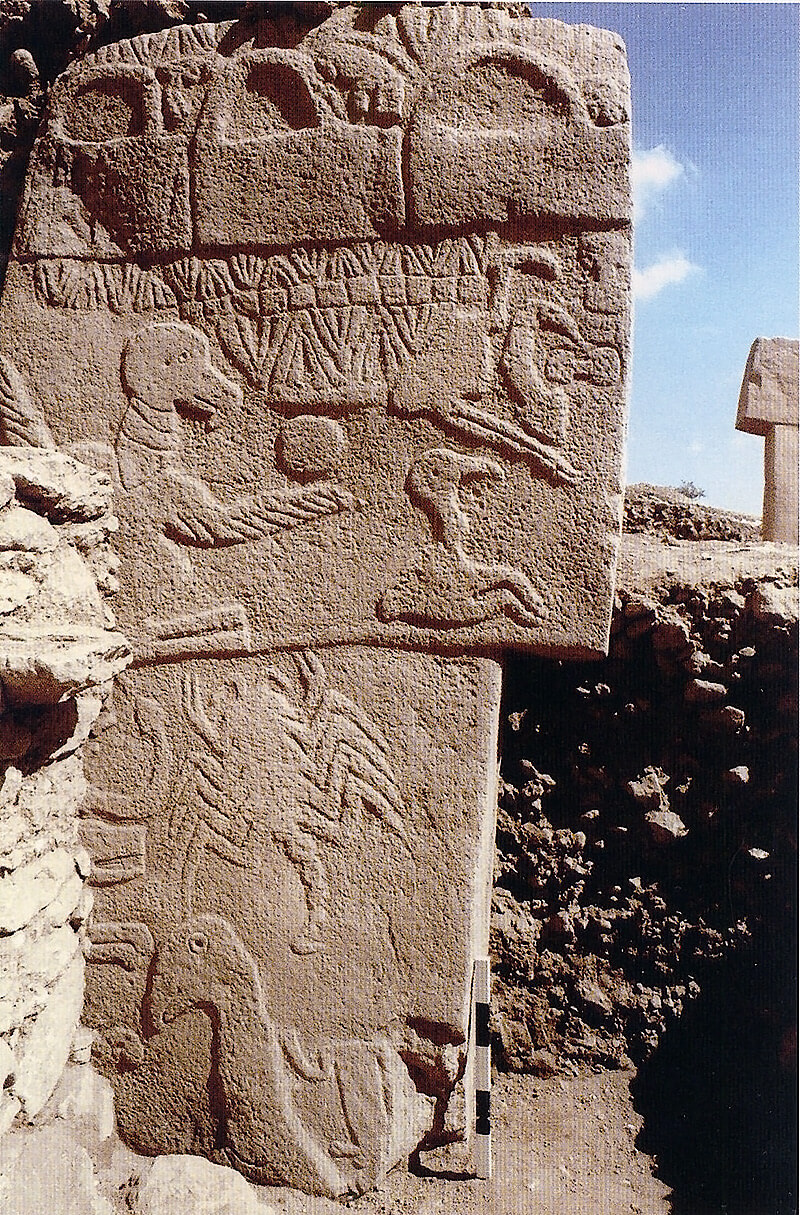

The oldest evidence of monumental megalithic art comes from the Far East, the Turkish locality of Göbekli Tepe. Several thousand circles were erected here 12 years ago with monolithic T-shaped columns in the middle. The stones and columns were covered with remarkable engravings of animals and beings combining animal and human parts. A similar style of art and architecture, albeit on a somewhat smaller scale, was discovered in nearby Nevalı Çori.

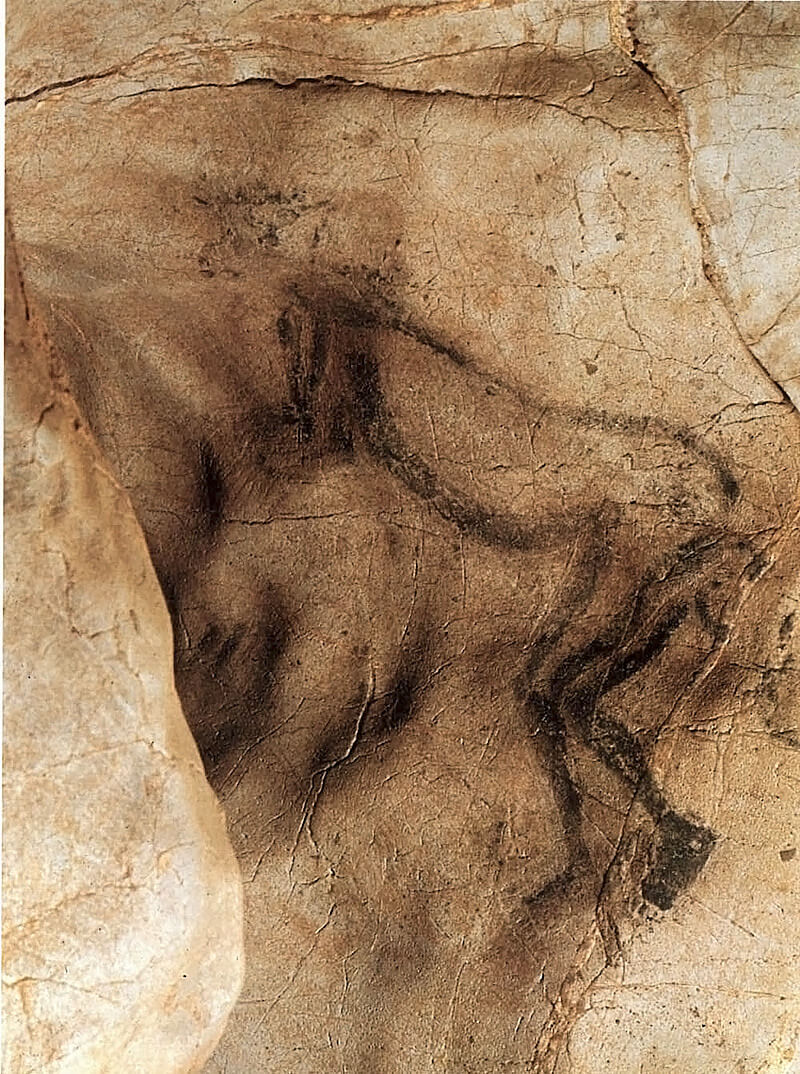

The Wizard of Trois-Frères in France

Around 7000 BC, a settlement was established on the Konya plain in southern Turkey, which provided an insight into the souls of prehistoric people and an understanding of many of their visions of the world and rituals. This settlement, called Çatalhöyük, consisted of houses built right next to each other, which were entered by a ladder from a flat roof. There were no streets and all social life took place either on the rooftops or in the dark of houses. An inexhaustible number of works of art in the form of murals, reliefs, bull-head sculptures and statues of goddesses have been uncovered in these dwellings. Beneath their floor were also evidence of complex funeral rituals by which the bearers of this long-extinct culture paid homage to their dead and ancestors. One of the frequent manifestations of prehistoric art was the depiction of so-called theriantrops, ie half animals, half people. These include the famous statuette of a lion man from Hohlenstein-Stadel in Germany or a cave painting by a wizard from Trois-Frères in France, but also a depiction of a half bird, half a man on one of the columns in Göbekli Tepe. The origin of these depictions could have been a deep trance in which the human soul leaves ordinary reality and enters another, sometimes called dreamy, in which a practitioner can experience a transformation into an animal or communicate with that animal. Such a transformation is one of the favorite themes of the art of cultures practicing ecstatic rituals, but it is also experienced by users of psychedelics. There are known cases where a person experienced the transformation into a tiger after ingestion of LSD and even saw himself as a tiger in a mirror. However, this is exactly the experience of being transformed into an animal, and some people experienced it in a dream and said that the feeling of 'being an animal' was very real for them.

A column from Göbekli beats depicting a half vulture, half a human

In the cosmology of prehistoric humans, animals played an important role as guides, counselors, and mediators of the transition between this and the dream world. This is evidenced by the breathtaking paintings in the Spanish and French caves, which probably do not represent real physical animals, but their spiritual representatives. For this reason, the choice of animals was relatively limited - only those animals were depicted that were of great spiritual significance to the people of that time and symbolized important parts of their cosmology. This idea is underlined by the modeled bull skulls in Çatalhöyük, which were located at the interface of the two spaces of the house - the entrance with the furnace and the elevated platforms - and thus separated the two symbolic spaces.

The murals in Çatalhöyük also depict vultures who represented the so-called psychopomps - beings who carried the soul of the deceased to the afterlife. This idea is also illustrated in one of the reliefs of the much older Göbekli Tepe. Funeral ceremonies involving the excarnation of selected individuals, a funeral custom known from present-day Tibet called air burial, could also be associated with vultures. The findings of individual skulls and headless bodies clearly indicate that the selected individuals were buried in a more complex way, which included placing the body and, after some time, reopening the grave and removing part of the remains. Moreover, this practice may have reflected the visions of the initiate during his initiation, the common part of which was the unraveling of the body consecrated by demons or animals and its reunification, followed by the rebirth of the initiate as a shaman.

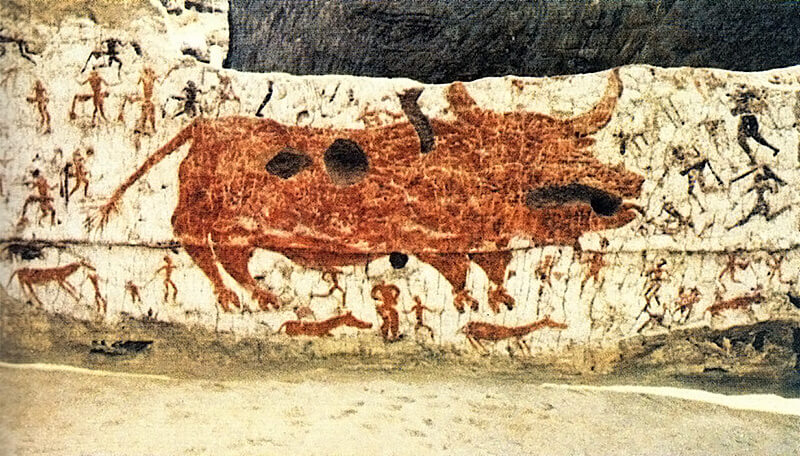

Scene of a bull hunt from Çatalhöyük

The importance of bulls for Çatalhöyük society is also emphasized by the depiction of bull hunting, which apparently represents not only real hunting, but also dancing with a sacred animal. On one part of the scene are hunters who surround a large bull and throw spears at it, on the other are dancers dressed in leopard skins. It is remarkable that some of the characters in the scene are headless. These figures probably represented significant ancestors, as indicated by the above-mentioned findings of bodies without heads or separate skulls. Thus, the bull was an important spiritual animal for the then inhabitants of the Konya Plain, whose sanctity is comparable to the significance of the bison for the original inhabitants of the American Great Plains, for which it represents abundance and revelation of the sacred order of the world.

The hidden message of prehistoric vessels

If we move to the Neolithic of Eastern and Central Europe, we find here in the period between 5500 and 3800 BC. prehistoric culture with richly decorated pottery. In Eastern Europe, more precisely in today's Romania, Moldova and Ukraine, it is the Cucuteni-Trypilja culture, in Central Europe it is followed by cultures with linear ceramics, spiked ceramics and the culture of Moravian painted ceramics, named after the typical decoration of their vessels. And it is precisely this typical decoration of vessels that gives us essential information about these long-defunct companies. Experts generally agree that the decoration of prehistoric vessels had more than just a decorative or practical function, and believe that it was a form of communication and maintained the tribal identity of society. The exact nature of the information encoded on prehistoric vessels is, of course, difficult to determine with certainty, but the very nature of the decoration can tell us a lot.

Prehistoric vessels: 1) culture with linear ceramics; 2) culture with spiked ceramics; 3) culture with Moravian painted ceramics; 4) Cucuteni-Trypilja culture

The most common decorative motifs are wavy lines, chessboards, spirals and geometric shapes, ie ornaments that do not commonly occur in nature. So the question is where these patterns came from. Although they look too abstract, they are by no means random, so it is clear that their creators knew why they chose this or that motif to decorate their vessels. If we return to the table on entoptic phenomena, we notice that a large part of these phenomena is imprinted in prehistoric ceramics. So it is quite possible that the world they wanted to capture is not the outer, but the inner. In their vessels, they reflected the world of altered states of consciousness and the optical hallucinations associated with it, from which they drew motives and which strengthened their sense of belonging to the community, with each culture highlighting a different entoptic phenomenon. In the case of the culture with linear ceramics or in the case of the Cucuteni-Trypilja culture, it was mainly a spiral; in the case of the culture with pointed ceramics, the crankshaft dominated and the culture with Moravian painted ceramics probably preferred a complex ornament called a hooked meander. What ornament prevailed in the decoration was determined by the cosmology of each individual culture, which connected these patterns with the transition to the world of dreams, another reality in which this cosmology was actually experienced.

A vessel of the Šipibo-Conibo tribe from Peru

For this claim, there is a very well-described parallel from the Amazonian Shipibo-Conibo tribe, who live a way of life not unlike the first farmers of Neolithic Europe, even though it is already greatly influenced by the penetration of Western culture. The Šipibo-Conibo tribe inhabits the Uyacali river basin in Peru and is best known for its textile art with beautiful, hand-embroidered, colorful patterns. The same patterns are found on their traditional pottery. In addition to the visual effect, however, the motifs on the ceramics and textiles of this tribe have another meaning. The Šipibo-Conibo tribe is famous not only for its beautiful works of art but also for its rituals with the sacred creeper of the yahé, also known as the ayahuasca. During these rituals, participants experience a profoundly altered state of consciousness accompanied by various sensory phenomena, including visual ones. And it is precisely these visual manifestations experienced during the yahé experience that are reflected in the traditional art of the indigenous people of the Amazon. However, these patterns also have a much deeper meaning by simply capturing the visions experienced. They record sacred ikaro songs, which not only accompany yahé ceremonies, but also use them on everyday occasions.

Thus, as can be seen from the example of the indigenous people of the Amazon, prehistoric people were able to record on their vessels their cosmology experienced during mystical initiation ceremonies. During them, they experienced profoundly changed states of consciousness in which they encountered spiritual beings, whether animal, human, or divine. The meeting with the mother divine being was probably significant for these people, as indicated by numerous female statuettes typical of the Cucuteni-Trypilja culture as well as for Moravian painted pottery.

A vision of the world immortalized in stone

In Eastern Ireland, about 40 km north of Dublin, there is a remarkable monument, famous for its very ingenious construction and preserved prehistoric art. These are the three tombs of Dowth, Knowth and probably the most famous of them, Newgrange. They were built about 5200 years ago and are therefore much older than the famous Stonehenge in southern England. The whole area is the richest site of evidence for megalithic art, with more than a quarter of megalithic art in Western Europe alone in the Knowth Tomb alone. This art is represented by engravings on the stones forming the inner and outer structure of the tomb and most often depicts motifs of spirals, checkerboards, rhombuses, zigzags and other abstract geometric shapes, which we also encountered on prehistoric pottery. As on it, here too art has captured the experience of passing into altered states of consciousness - the world of gods, ancestors and sacred animals.

Newgrange Tomb in Eastern Ireland

However, the very construction of these tombs helps to reveal other secrets of ancient people and their perception of the world. The tombs are mostly formed by a stone corridor built of massive monoliths, which support the ceiling stones. This corridor either ends roughly in the middle of the tomb or opens into a chamber in the shape of a cross, the ceiling of which is built by the method of false vault. This means that the individual stones were placed so that they always protrude into the center of the space until it completely overlapped. On this massive structure, clay was subsequently piled up in the form of a mound, and its perimeter was in some cases provided with other megaliths, some of which were richly decorated. In addition, Newgrange's tomb contained a very remarkable building element telling of the ingenuity and astronomical knowledge of the ancient inhabitants of Ireland. During the sunrise at the winter solstice, a beam of light penetrates a small hole into the center of the tomb, where it illuminates a megalith decorated with the iconic motif of this monument - a triple spiral. The tombs were also equipped with stone bowls, in which the remains of ancestors were probably placed in one phase of the funeral or memorial ritual.

Detail of the decoration of one of the perimeter stones of the Newgrange tomb

The ideas that immortalize tombs like Newgrange directly refer to the traditional conception of a world composed of three main parts - the upper world inhabited by gods, the middle world of humans and the lower world, in which ancestors and spiritual animals reside. Entry into the interior of the tomb, which was probably only allowed to a small group of initiates, therefore represented not only entry into the physical underworld, but also into the spiritual. It was an entry into the world of ancestors, into the deepest level of the human psyche associated with the subconscious. Aaron Watson, an archaeologist focusing on archeology, among other things, wrote: “By entering these monuments, the participants were clearly separated from the outside world. . ‟

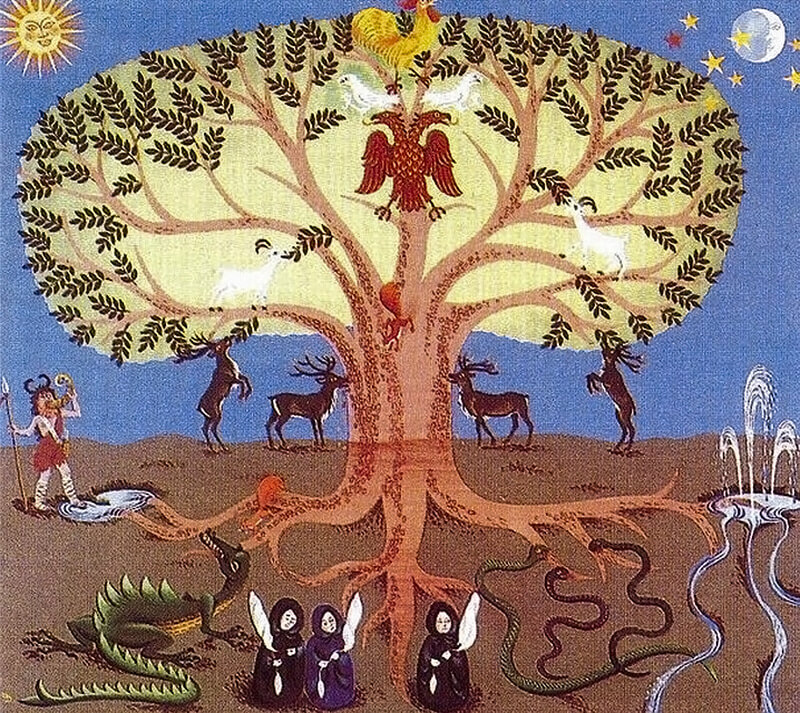

Artistic rendering of a tree of the world

The division of the world into three parts is characteristic of almost all traditional societies and prehistoric cultures, but also historical ancient civilizations, such as Sumerian. In this concept, the axis of the world is formed by a sacred tree in the crown of which is the upper world, most often symbolized by an eagle. In the roots of this tree is then located the lower world represented by the snake. This concept appears in certain variations from Siberia to the Amazon and is therefore universal for all mankind. In many cultures, human dwellings are also a model for this understanding of the universe, as is the case with the Amazon Barasana tribe, whose long houses contain building elements that have no practical purpose but serve to capture their cosmology. In this sense, the roof represents the heavens, the pillars of the house the mountains that support the heavens, the floor is the earth, and beneath it is the underworld. The same idea, but in a far more monumental form, was therefore imprinted in the megalithic tombs.

Tips from the Sueneé Universe e-shop

How to know your guardian angel and his energy? Angels protect us, give us warmth or warn us.

6

6