Egypt: Radiocarbon dating of the Old Pyramid

25. 11. 2017

25. 11. 2017

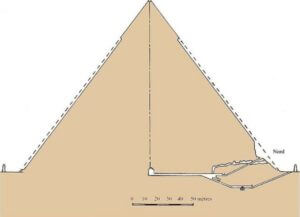

Robert Bauval: Until the end of 1993, it was generally believed that no artifacts or monuments of any kind could be found in the Pyramids of Giza that could date from the same period as the construction of the monuments, and that as a result no organic material such as wood was available to scientists. , human bones or textile fibers which may have been used for dating the pyramids by the radio carbon carbon C method14 (further: dating C14)

We know of certain suspicious artifacts found in the pyramids of Giza, which, if they survived, could be used to date C14. Abu Szalt, a medieval Arab chronicler from Spain, for example, reported that when Caliph Ma'amoun first entered the pyramid in the 9th century and went to the space in the so-called royal hall, "... the lid was forcibly opened, but nothing was discovered, except for some bones that were completely disintegrated by age.“[2] In 1818, when Belzoni entered the second pyramid (the so-called " Chefre), found several bones inside the sarcophagus, which obviously belonged to the bull. Also during the expedition Howard Vyse 1836-7 found a relic inside the third pyramid. Menkaure), consisting of human bones and parts of the lid of a wooden coffin. But dating C14 revealed that the bones come from the early Christian era and the lid was determined to be from the period Saite. Expedition Howard Vyse also when looking at the outside middle pyramid discovered another strange artifact with explosives. An iron plate measuring 26 x 8,8 cm and approximately 4 mm thick. Although the iron cannot be dated to C14, the story of its discovery and testing in terms of possible enormous clues that may have borne the age of the pyramid must be recalled.

In 1989, however, two metallurgists, Dr. El Gayar from the Petroleum and Mineral Faculty in Suez, Egypt and Dr. MP Jones from Imperial College London asked the British Museum for a small sample of iron so that they could conduct full scientific research. After El Gayar a Jones made a number of chemical and microscopic tests on the iron plate, these scientists concluded that: "The slab was incorporated into the pyramid at the time of construction", ie it was from the present time with the pyramid [6]. Chemical and microscopic iron plate analyzes also revealed very small traces of gold, indicating that the plate was originally gilded. The actual size of the board was estimated to be 26 x 26 cm, which is roughly the same size of the shaft's back, which in turn indicates that the board may have served as a cover or a gate to the shaft. El Gayar a Jones they also pointed out that the size of the 26 x 26 cm plate indicated that it was measured at the royal elbow, a measure used by the builders of the pyramids (half of the royal elbow 52,37 cm is 26,18 cm).

As already mentioned, C14 could not be dated to the board because it contained no organic material. Despite the findings Gayer a Jones, The British Museum still assumes that the iron plate was probably a piece of a broken shovel used by the Arabs in the Middle Ages.

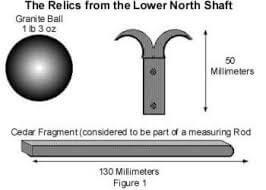

Dixon's relic

In September 1872 he was a British engineer Waynman Dixon, working in Egypt, asked Piazzi Smyth, a royal astronomer from Scotland, to carry out some surveys for him inside the Pyramids of Giza. [7] Around that time, Dixon discovered the openings of two shafts on the south and north walls of the so-called The Queen's Chamber. In the horizontal part of the shafts that lead to the chamber, Dixon found three small relics: small bronze hook, part of "cedar" wood and granite spheres. [8] The relics were packed in a wooden cigar box and transported to England John Dixon, Waynman older brother, also an engineer. Were sent Piazzi Smyth, which recorded them in the diary, then returned to John Dixon, which eventually arranged the publication of the articles and drawings of the relics in the scientific journal Nature and in the popular London newspaper The Graphic. [9] Dixon's relic then mysteriously disappeared. Surprisingly, although the discovery of the shaft, The Queen's Chamber Waynman Dixon has been announced yet Flindersem Petriem in 1881 and Dr. IES Edwards in 1946 and for several years by other pyramid specialists, Dixon's relic they were never mentioned again and their existence was clearly forgotten. The only person, if I may write it like this, who mentioned these relics after they were published in December 1872 in Nature and The Graphic was an astronomer. Piazzi Smyth. (see below)

Here's what really happened with relics after December 1872: exactly a hundred years later, in 1972, a certain lady Elizabeth Porteous, living in Hounslow near London, was warned (probably because of the turmoil about Tutankhamun exhibitions at the time) that her great-grandfather John Dixon he left his family a cigar box in which the relics were found in The Great Pyramid, which she inherited in 1970 after her father's death. Ms Porteous then she took the relics, still in the original box, into Of the British Museum. They were registered by Mr. Ianem Shore, then Dr. Assistant IES Edwards, curator of the department Egyptian antiques. However, probably due to the stir caused by the exhibition Tutanchamon, were Dixon's relic founded and forgotten.

In September 1993, when I came across a comment Piazzi Smytha In one of his books [11], I decided to find out where Dixon's relic they find. I contacted Dr. IES Edwards (he then retired from Oxford) and also Dr. Carola Andrews a Dr. AJ Spencer z Of the British Museum, but none of them seemed to have heard of these relics. Finally with help Dr. Mary Bruck, biographer Piazzi Smytha[12], I tracked a personal diary Piazzi Smytha v Ediburgh Observatory and I found his record of the relics of 26. November 1872, as well as the private letters he has received since John Dixon at the time. Through these documents, I then found articles published in Nature a The Graphic.

While I was still searching for the relics, I remembered it was John Dixon, who in 1872-6 arranged for the transport of the obelisk of Thotmose III. (Needle Cleopatra) on the waterfront Victoria in London and, more importantly, he had under his pedestal John Dixon ceremonially save different sights including cigar boxes! Of course, many of us began to suspect that it could be the same cigar box that contained ancient relics found in the so-called shaft. The Queen's Chamber ve The Great Pyramid. Fortunately, that was not the case.

At that stage of the search, I decided to publish an article in a British newspaper The Independent[13] in the hope that someone might remember where he was Dixon's relic. This tactic worked. Ian Shore, who registered the relics in 1972 at the British Museum, read the article and remembered that they had been donated to Mrs. Porteous. He immediately informed Dr. Edwards, which turned to Dr. Viviana Daviese, curator of Egyptian antiquities in the Bristol Museum. The search began and the relics were re-discovered at the British Museum in the second week in December 1993[14]. Unfortunately, he was missing a small piece of cedar wood, and therefore it was impossible to date C14. The relics are now on display in the Egyptian section of the British Museum.

We will all remember that in March 1993, a German engineer Rudolf Gantenbrink he explored the so-called " The Queen's Chamber in the Great Pyramid using a miniature robot equipped with a video camera. He was amazed to find that the northern shaft had been examined (probably by Dixon) with a metal rod (assembled in sections of metal), the remains of which were still visible in the shaft.

- John Dixon: Revealing Rods

- John Dixon: reconnaissance rods assembled into one another

The metal rod was pushed about 24 meters deep into the shaft until it reached a point where the shaft turned sharply to the west and formed an almost rectangular corner. Also in this Corner it was to be seen what seemed to be a long piece of wood whose shape and overall look seemed to be the same as the shorter piece he found Dixon's team in 1872 at the bottom of this shaft.

Dr. Zahi Hawass: Intrigue in the Background of Egyptology (1.)

Colovy relikvie

1946 was a British chemist Herbert Cole, who was stationed with the British Armed Forces in Egypt, called upon to secure fumigation the second pyramid in Giza, which was closed during the war. Cole he built his equipment in the Pyramid so that the legs of many extraction fans were fixed to the open joints of the original limestone blocks. As he did so, he noticed that several were stuck inside one of the joints pieces of wood a bone bones[15]. Cole he took those relics back to England, where they remained in his house in Buckinghamshire until his death in 1993. A few years later, his son, Mr. Michael Cole, which read about Dixon relics in my book, he decided to contact me and sent me on October 5, 1998 finger and a piece wood. From him I discovered that his father was before the War of the Technical Director of the London Fumigation Society, and returned to this place after the war. In 1946 it was Herbert Cole located in Alexandria, where he was responsible for the fumigation of Britain's supply ships. At the end of 1945 or early 1946 was Herbert Cole asked to ensure fumigation of the middle pyramid. According to his son Michael:

Fumigation was carried out using pressurized hydrogen cyanide to ensure access to all cracks, etc. Suction units were installed ... During the installation of these units, which included inserting the supports into some spaces between the pyramid blocks, a piece of wood a piece of bone, which was identified as part of the finger, were pulled out of the two blocks. The wood immediately split into four pieces, three of which were held by my father. I attach the bone and the middle piece to this letter. My father claimed that these were found in a position that could be identical to the construction of the pyramid. His theory is that the bone was part of the hand of a worker who was trapped between blocks when they were put in place.

The first thing I did was visit Michael Coleto look at the remaining pieces of wood. Michael Cole he then gave me finger a one piece of wood, which he sent me earlier, trying to test C14. A few days later, I took the sights of the British Museum and showed them to the doctor Vivian Daviesto see if he could organize C14 testing. Doctor Davies suggested that I take them to Dr. Hawass in Egypt.

Herodotus, who visited Giza in 5. century BC, apparently did not see any entry into this pyramid [18]. He announced the same thing Diodorus Siculus (1 century BC) a Plinus older (1 Century AD) [19]. That is why it was supposed to middle pyramid it was first penetrated in ancient times, probably in the first middle period, and so its entrances were eventually obscured and forgotten. [20] However, the pyramid could still be closed when Herodotus visited Giza in 450 BC? And if so, it could be opened for the first time and plundered v Ptolemaic times? Still, why the inputs were not seen Diodorus in 60 BC?

However, it is known with certainty that they entered the middle pyramid for the first time Arabs, maybe in 13. century, through a carved tunnel that was embossed on the northern side of the monument above the original upper entrance. [21] There are no records of this event, except for the crude graffiti found on the walls of the two chambers.

The entrances were strangely forgotten or covered again, perhaps by the bursting of cladding blocks, which brought about a great earthquake that struck the Cairo region in the 13th century AD Arabian tunnel and reopened the two original inputs Belzoni in 1818, which cleared only the upper original input to enter the pyramid. Later, in 1837, Howard Vyse cleared the lower original input.

Interestingly, the result of the C14 test for the finger bone found Herbert Cole (designated A-38550), gives the date 128 ± 36 BCE (without comparative calibration) and, after calibration, sets it between about 1837 to 1909 of our time. The lower date of 1837 is interesting because it falls exactly at the time Howard Vyse he dug the way into this pyramid using explosives, so there is a strong possibility that he can finger comes from the hand of one of his unhappy Arab workers.

Another investigation

Given the endless discussions about the exact age and purpose of the Giza pyramids, as well as the unclear and uncertain history of when and how they were first disrupted and looted, such ancient or modern relics as described above can provide us with much information, not least through dating. C14, but also using other scientific techniques, such as DNA analysis and new state-of-the-art forensic methods.

Even more important is that in the hitherto unexplored northern shaft, the so-called The Queen's Chamber The Great Pyramids remain many things as we have seen: wooden stick, which was almost certainly left by the original builders. [22] And, of course, even more interesting would be the opening of so-called " the door at the end of the southern shaft, which were discovered in 1993 by Rudolf Gantenbrink [23]. This Door, which are made of highly polished limestone, has two small bronze or copper pieces embedded in their structure bronze the tool he found Dixon in 1872 at the bottom of this shaft.

What is behind them is the 64 question of thousands of dollars of pyramid archeology.

[Hr]

Sueneé: Today we know that there is less room and another door behind the first door. From this space, images were taken using a small camera.

- Illustration of space

- Composition of space photos

- Detail of found symbols

- The other side of the door

Notes by Robert Bauval

[2] Retrieved Mark Lehner in Complete Pyramid, Thames & Hudson 1997, p. 41

[3] Ibid. 124. Rainer Stadelmann believes that these bones were inserted into the sarcophagus as some "Osirian gift" long after the pyramid was disrupted. As far as I know, these bones have not dated C14 to verify this hypothesis.

[4] IES Edwards, The Pyramids of Egypt, 1993 ed. 143. The wooden lid is in the British Museum.

[5] A. Lucas, Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries, HMM London, 1989, 237

[6] El Sayed El Gayar a MP Jones metallurgical survey of an iron plate found in 1837 in the Great Pyramid of Giza, Egypt, in the newspaper of the Historical Metalurgy Society, vol. 23, 1989, pp. 75-83.

[7] C.Piazzi Smyth, Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid, 4. edition, page 427-9. Very close and friendly cooperation between the two brothers Dixons and Smythem is visible in the extensive correspondence between them, most of which were stored in the archival library Edinburgh Astronomical Observatories. See also The Orion Mystery Epilogue (Heinemann 1994), where part of this correspondence is reproduced.

[8] Piazzi Smyth op.cit. p. 429. Confirmation that "cedar wood" and a granite ball were found in the northern shaft and a "bronze hook" in the southern shaft is provided John Dixon in an interview he gave to Mr HW Chrisholm, Warden of the Standards, who reported his testimony in an article in NATURE on December 26, 1872. However, in a private letter Piazzi Smyth, dated 23. November 1872 after describing the shafts in the so-called " royal chamber, Dixon wrote: "We found these tools here, in the north shaft." Whereas the John Dixon he described bronze hook elsewhere like some tool, there is doubt as to which of the shafts was found. John Dixon was not witnessing the opening of the shafts and relics discovered by his younger brother Waynman in September 1872. Unfortunately, the detailed report apparently submitted by Waynman at the end of 1872 Piazzi Smyth, was lost.

[9] NATURE, 26. December 1872, page 146-9. GRAPHICS, 7. December 1872, 530 and 545.

[10] Look Into The Independent 6. December 1993, p. 3. Dr. IES Edwards was quoted as saying: "The existence of relics has been forgotten. They are a complete novelty for me. I've never met anyone who has ever heard of these things. " This fact was confirmed to me by various staff at the British Museum during a special presentation Rudolf Gantenbrink on BM on 22. November 1993 (also faxed to me by Dr. Carol Andrews of 24 October 1993). Searching for relics began in collaboration with Dr. IES Edwards, Dr. MT Bruck from Edinburgh and Dr. Carolem Andrews a Dr. Spencer from the British Museum. The relics were eventually traced in December 1993.

[11] Robert Bauval & Adrian Gilbert, The Orion Mystery, William Heinemann 1993, epilogue.

[12] Mary T. Bruck a Hermann Bruck, The Peripatetic Astronomer, Adam Hilger, Bristol 1988. As Piazzi Smyth he was before him Hermann Bruck in the 1960s by the Royal Astronomer himself.

[13] The Independent 6. December, 1993.

[14] The Independent 15. December, 1993, letter from V. Davies. See also Ibid. 29. December 1993 letter R. Bauvala. Also Ibid. Jan.11, 1994, Mrs. Letter E. Porteous.

[15] The bone is from the thumb of the left hand.

[16] M-Net TV from South Africa, producer and director D. Lucas.

[17] The remains were tested by Dr. Mitzi De Martino at AMS Facility, Arizona University, Department of Physics.

[18] Herodotus, History, Book II, 127

[19] L. Cottrell, The Mountains of Pharaoh, Book Club Assoc. London 1975, 116.

[20] M. Lehner, The Complete Pyramids, Thames & Hudson 1997, 124.

[21] Ibid. Str. 49.

[22] Doubts about the origin of this wood were raised by Dr. Hawassem, who claimed that it could have been located there in modern times only after the opening of the shaft Wayman Dixon in 1872. However, this is unlikely. This wood has a length of about 80 cm and a rectangular cross section of about 1,25 x 1,25 cm. It lies opposite the small south wall corner lengths northern shaft (about 24 meters upwards, where the shaft spins steeply to the west, making this small corner length and protrudes about 30 cm into the main shaft, its end is clearly broken off. This position makes it impossible for it to be located there in modern times. There are also small pieces of limestone on the top of the wood, which are, of course, chips that fell to the mason during construction. Also a mysterious resemblance to the shape of this wood with a 12 cm long piece found by Dixon at the bottom of the north shaft, which also has a rectangular cross measuring 1,25 x 1,1 cm, which was marked as part of the measurement length) is almost certain that both pieces belong to the same poles. Absolute confirmation of this fact can only be accomplished by pulling this piece from the northern shaft and dating C14. We can do this also determine the exact age of the Great Pyramid.

[23] Look at R. Stadelmann, Die sogenannten Luftkanale der Cheopspyramide Modellkorridore für den Aufstieg des Konigs zum Himmel, in MDAIK Band 50, 1994, str. 285-295.

1

1