La Rinconada - a city called Hypoxia

04. 11. 2019

04. 11. 2019

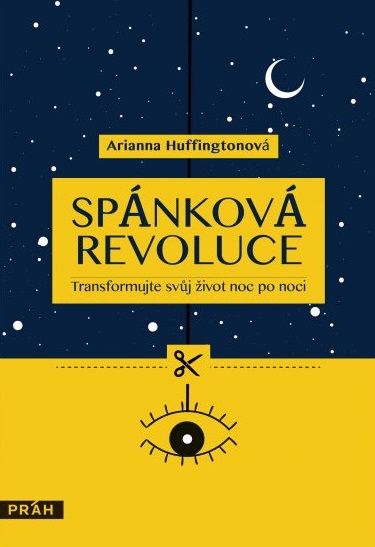

Peruvian city, famous for gold mining, is with its altitude 5100 m asl the highest settlement in the world - and a good place to study how life at extremely low oxygen levels damages the human body.

Provisional laboratory

One cold, gray morning earlier this year, Ermilio Sucasaire, a miner in gold mines, was sitting in a white plastic chair with a pile of papers and a pen in his hand. His inquisitive eyes followed a large room where a group of scientists were conducting tests on his co-workers. One colleague was pedaling the bike, barely holding his breath, the electrodes attached to his chest. Another man took off his dirty sweater and lay covered on a wooden bed; a European scientist pressed a tool to his neck and looked at his laptop.

Sucasaire was next - after signing the consent form and completing a long questionnaire about his health, life, work history, family, drinking, smoking and coca chewing habits. "I'm looking forward to it," he said.

The corner place

Scientists, led by physiologist and mountain enthusiast Samuel Vergès of the French biomedical research agency INSERM in Grenoble, set up a temporary laboratory in southeastern Peru in the highest human settlement, at a mining center for gold mining at 5100 meters. There are an estimated 50 000 to 70 000 people trying to find gold and get rich, but in very brutal conditions.

La Rinconada has no running water, no sewage system or garbage collection. The city is heavily contaminated with mercury, which is used in gold mining. Working in unregulated mines is difficult and dangerous. Drinking, prostitution and violence are common. Freezing temperatures and intense ultraviolet radiation add to the difficulties.

CMS

However, the most important feature of the city that attracted scientists so much is thin air. Each breath contains half the oxygen here, compared to taking a breath at sea level. Continuous oxygen deprivation can cause a syndrome called Chronic Mountain Disease (CMS), characterized by excessive red blood cell proliferation. Symptoms include dizziness, headaches, ringing in the ears, sleep problems, shortness of breath, palpitations, fatigue and cyanosis, which stains lips, gums and hands in purple blue. In the long term, CMS can lead to heart failure and death. This disease cannot be cured unless you return to lower altitudes - although some symptoms may already be permanent.

CMS is a serious health threat to roughly 140 millions of people living above 2500 above sea level In the capital of Bolivia, La Paz, which lies at an altitude of 3600 meters, an estimated 6 ˗ 8% of the population - up to 63 000 - suffers from CMS. Some cities in Peru account for up to 20% of the population. But La Rinconada leads all the way; scientists estimate that At least one in four people suffer from CMS. Like many other chronic diseases, CMS receives less attention from healthcare institutions, says Francisco Villafuerte of Cayetano Heredia University in Lima. "Although one third of Peru's population lives above 2500 meters, it is a neglected disease here," says Villafuerte, who has not taken part in the study at La Rinconada, but is engaged in CMS.

How to treat CMS?

According to Vergès, the right treatment would be very helpful. But in order for scientists to develop it, they first need to understand what leads to a reduction in red blood cell production, how it affects the body, and why it is only a problem for some people. Researchers also want to find out what genes are involved in this process and how they have been shaped by modern human evolution. A deeper understanding of CMS can also help patients with cardiovascular disease who also suffer from a lack of oxygen, says cardiologist Gianfranco Parati of the Italian Institute of Auxology in Milan, whose colleague Elisa Perger participated in the study.

French cardiologist Stéphane Doutreleau performs a cardiac examination of Ermilia Sucasair, a miner in the gold mines.

To get answers to these questions, the INSERM team delivered € 500 worth of scientific equipment and a 000-day scientific mission here in February on a muddy bumpy road. The plan was to compare 12 men from high altitudes suffering from CMS with 35 local healthy residents and several also healthy people living at lower altitudes. It was a scientifically and logistically unprecedented event. Peru boasts a long history of CMS research - the disease was first described in 20 by the Peruvian physician Carlos Monge Medrano. However, most scientists operate at a significantly lower altitude of 1925 meters, in the mining town of Cerro de Pasco in the central Andes. A study at La Rinconada altitude has not yet been carried out.

Sucasaire heard about the study on local radio. He was one of the hundreds who came to the lab in a dilapidated building owned by the Miners Association, hoping to get into the study. If selected, it will undergo several days of testing, including blood and blood analysis circulation, function of the lungs, heart and brain and the body's reaction during exercise and sleep.

Like other trainees, Sucasaire hoped to receive medical examinations and possibly treatments. La Rinconada has only one health clinic that cannot keep up with the growing population. "My knees," said 42, the old miner, "are sore and swollen. I can't go uphill, I'm having trouble climbing stairs. I hope the doctors can help me. ”

We can manage a short stay, but a long stay is a problem

A few minutes of denial of oxygen results in irreversible brain damage and death. But simply reducing the oxygen level, if it is only short-term, we can handle remarkably well. Yes, people used to living in the lowlands often suffer from acute mountain disease, including headaches and nausea, at altitudes above 2500 meters. (Many Peruvian hotels have oxygen on hand for impoverished tourists.) But the symptoms begin to subside in one or two days. The body adapts by creating a bunch of extra red blood cells, which then convert oxygen-bound hemoglobin into organs and tissues.

However, a long stay at high altitude is more complicated. Many lowland people have a problem to increase their oxygen consumption enough to live there permanently. Particularly problematic is reproduction - which the Spaniards have already discovered during the colonization of the Andes. In pregnant women, hypoxia often leads to preeclampsia, which can endanger the mother and the baby. Other consequences are premature births and low infant weight. The population that has lived in the high mountains for hundreds of generations is much better off.

And the inhabitants of the Andes have been living at high altitudes for about 15 000 for years, and like the Tibetan plateau or the East African Highlands, their organisms have evolved to cope with hypoxia due to complex physiological changes. Over the past decade, scientists have identified several genes that are responsible for these changes. They can be divided into three independent groups; in Andes, a key change is the increased hemoglobin level that allows their blood to carry more oxygen. However, in some people, with red blood cell proliferation, this level rises out of control, leading to CMS.

Ermilio Sucasaire owns a simple house in La Rinconada without heating, water or sewage (left). As part of a study to measure total hemoglobin volume, he inhaled a small piece of carbon monoxide (right).

Excess red blood cells

This excess of red blood cells makes the blood more viscous and strains the circulatory system. (Some people's blood has a near tar consistency here, so it is almost impossible to take serum samples.) Blood vessels, usually dynamic tubes, that widen as needed, are spread permanently. Blood pressure in the lungs often increases. The heart is overworked.

Other high altitude groups have adapted to low oxygen levels without significantly increasing hemoglobin and are less affected by CMS. For example, Tibetans are mainly more frequent and deeper breathing. A study in Native Tibetans from 1998 found the incidence of CMS in only 1,2% of participants. In several studies conducted in Ethiopian highlanders, CMS was not found at all. In contrast, a study in Cerro de Pasco found a prevalence of CMS to 15% in men between 30 to 39 years and 33% in the age of 50 to 59 years.

There is no proven treatment. One solution practiced in Peru is phlebotomy or venous drainage; relieves symptoms for a few months, says Villafuerte. However, this procedure is cumbersome and further deprives the body of oxygen - which could, counterproductively, stimulate even faster red blood cell production.

Several drugs have also been tried. One of them, acetazolamide, is also used for acute mountain sickness. It works by acidifying the blood, which stimulates breathing. Two studies in Cerro de Pasco have shown that the medicine decreases the hemoglobin content of the blood and increases oxygen saturation. But even the most extensive study, published in 2008, involved only 34 people and lasted only 6 months. It is unclear whether the long-term benefits outweigh the side effects. "You would have to take this medicine while you are living at high altitude," says Villafuerte.

The corner place

LA RINCONADA lies 2,5 hours of jerky driving from Juliaca, a dull transit center with 250 000 residents, located at 3825 meters above sea level.

La Rinconada, a city in the Andes in southeastern Peru, lies at an altitude of 5100 meters. Nearby cities like Juliaca and Puno lie at about 3800 meters above sea level

Peruvian physician and research team member Ivan Hancco came to 2007 for the first time while studying medicine in Puno, a nearby town and a tourist destination on Lake Titicaca. He was more interested in research than clinical work, attracted by altitude sickness, but he didn't know much about La Rinconada. Few know about it in Peru, he says. “I thought it was a small town. I had no idea. ”

Only when Hancco was walking down the busy main street could he say that the CMS was a much bigger problem than in Pune, 1300 meters below. "Red eyes, purple lips and hands were visible everywhere," he recalls. He began to come here more often, first monthly and later every two weeks, to offer medical assistance to the residents and to carefully record their complaints. The result was, as Vergès says, a unique long-term database of CMS and other health problems, involving more than 1500 people. (Researchers published a paper on the findings of this database in a journal.)

Vergès also grew up at high altitude in the French ski town of Font-Romeu-Odeillo-Via in the Pyrenees, at an altitude of 1800 meters. Thanks to the high-altitude training center, it has become a popular destination for European athletes. Vergès himself was on the national ski team for several years and studied sports science and physiology at the University of Grenoble. In 2003, he received his Ph.D. for his work on respiratory dysfunction in endurance athletes, in which he used his former teammates as study subjects.

Simulation of short stay

Most of Vergès's studies take place in his laboratory in Grenoble, where he can simulate short-term stays at high altitude using a mask or tent with a low oxygen content. But his heart beats for field work - literally. In 2011, he hired a helicopter and took 11 healthy men to a research station in Mont Blanc, France, at an altitude of 4350 meters. Here he measured their blood flow to the brain and other parameters during 6 days. (Nine of them, as well as Vergès, fell ill.) In 2015, he took part in a 10-day expedition to Tibet to observe 15 long-term hypoxia at 5 meters.

The study in La Rinconada was scheduled in 2016 at a meeting of scientists in the French resort of Chamonix near Mont Blanc, to which Vergès also invited Hancca. The two sat down. Hancco decided to finish his studies in Grenoble and is now working on a doctorate at Vergès Laboratory. Both scientists say that Hancc's contacts in La Rinconada, along with the confidence he has built up there in providing medical care, have been a major contributor to the study. Hancco helped ensure logistical support, including from César Pampa, President of the Mine Owners' Association. (Pampa lived in La Rinconada for years, but moved to Juliaca because of CMS, which seriously threatened him.) "It was a unique opportunity," Vergès says. "A dream come true."

Vergès had no grant for this study, but found sponsors, including one mountain clothing company. She equipped the team with clothing with the inscriptions "Expédition 5300". (It was a little exaggerated; one peak above La Rinconada has 5300 meters, but the city and most of the mines lie in 5100 meters). Scientists commissioned a professional video and presented the study as a “unique adventure”. As soon as they arrived in Peru in early February, they started informing their French audience through videos. The videos showed a hard-breathing team of scientists conducting miners' tests on the steep streets of La Rinconada.

Research leader Samuel Vergès thanks and presents one of the 55 participants in the study in La Rinconada.

La Rinconada is the least bad choice

Sucasaire, born in one of the villages in the Peruvian Highlands, first came looking for a job in 1995. He was 17 years old. He has since left several times since, for example, trying his luck at a coffee farm in northeastern Peru. In the end, he decided that despite the harsh conditions, La Rinconada was the least bad choice. "It's a forgotten city," he says. "The government is not interested in us at all. He thinks only of his own interests. We have to find a way to survive ourselves. "

Sucasaire belongs to the indigenous tribe of Aymara, living in Peru, Bolivia and northern Chile. Because his ancestors lived in the highlands for many generations, he will probably have genetic traits that help him live at high altitudes. However, evolution did not prepare Sucasaira for life in La Rinconada. In the initial tests, the results of seven symptoms combined with higher hemoglobin levels showed the presence of CMS, so he agreed to be included in the study. He had to return to the center for several days for testing, which often took hours.

In one experiment, Sucasaire inhaled a small amount of carbon monoxide, a toxic gas that binds to hemoglobin to determine the total amount of hemoglobin in his blood. In the second, he had to lie patiently on his right side while the French cardiologist Stéphane Doutreleau studied the echocardiography of his heart.

Sleep study

One evening, Sucasaire came to a sleep study conducted by Dr. Perger. She clipped electrodes to his chest to monitor his heart rate and equipped him with a monitor to record the breath and any episodes of sleep apnea that is commonly found in hypoxia. The wires led to a small recorder attached to the wrist. A small blue device that monitored the oxygen saturation in the blood snapped to the tip of his left index finger. Then the doctor sent him home. It wasn't the most comfortable way to spend the night, but Sucasaire said he would sleep "con los angelitos" - with angels.

Sucassaire lives 10 minutes by walking through muddy streets and trails from the lab. One room house he shares with three adult relatives is actually a shack, window-less corrugated iron he bought 7 years ago. It is one of thousands of similar houses scattered on the hillside. The niece cooked dinner on a portable gas burner. Although it was summer, the beds were filled with blankets; the house has no heating and the previous night the snow fell. "We just cover up very well," Sucasaire said. The family uses the nearby stinking public facilities as a bathroom. Drinking water has to be bought and it's very expensive, Sucasaire said.

It works in the 20 Mine a minute walk from the city. The way to the entrance is lined with huge mountains of garbage wrapped in small plastic bags. Foreign entry is forbidden, he said.

Gold mining

Many Peruvian mines are operated by large international companies, but gold mining in La Rinconada is "unofficial" or illegal. Sucasaire works 5 or 6 hours a day; It's such a hard job that working longer is physically impossible, he said. They are afraid of mine dust, moisture and carbon monoxide. "Some of my colleagues died young - at 50, 48, 45 years," he said. The fatal consequences of explosions and the collapse of tunnels are common here. "There is no security mechanism," says César Ipenza, an environmental lawyer based in Lima. "That's why there are frequent accidents."

Most mine owners do not pay their employees a salary; instead, one or more days in each month allow them to take home any ore they carry in 50 kg bags. They can keep the gold in it. This system, called cachorreo, turns life into a huge lottery; Ipenza calls it a "form of slavery." Some miners "get a decent amount of gold," Sucasaire said, "and some leave the city." It's a minority. Usually miners only find enough to survive. Sometimes they find almost nothing.

Women are not allowed in the gold mines in La Rinconada. Many try to make a living by finding a little gold in the discarded stones.

Miners take their ore to one of the many small shops in the city that advertise "compro oro" ("buy gold"). To separate the gold, merchants mix it with mercury to form an alloy. Then, using a burner, the mercury evaporates and small clusters of pure gold are separated. Vapors seep through the narrow metal chimneys and create a toxic cloud that covers the city and the nearby glacier, which is the main source of water.

Women are not allowed in mines

Women are not allowed in mines, but there are several hundreds living nearby. On a steep slope sat Nancy Chayña smashing stones with a hammer. She carefully checked each piece for glittering stains. She threw the glittering ones into a yellow sack. Chayña said she has been working in rubble for about 20 years, at least 10 hours a day. Her heavy clothes were dusty, her face showing traces of icy wind and intense sunlight. Asked if she'd rather work in the mine, she laughed and said yes. But women in the mines are said to be unlucky, Sucasaire noted. In addition, this work is considered too dangerous for women.

The Peruvian government plans to 'formalize' illegal logging, which could help improve working conditions. But it hasn't happened yet. This idea is opposed by the owners of the mines and it would not bring much to politicians as well. So Sucasaire doesn't believe that this will ever happen.

Staying in LA RINCONADA was difficult

Staying in LA RINCONADA was also difficult for the research team. Of course, hypoxia in some of them also caused shortness of breath, exhaustion and problems with concentration. Vergès slept badly and woke up several times a night, gasping for breath. There was a foul odor in the streets - a mixture of human waste and old frying oil - and decent food was hard to find. The researchers usually withdrew to their hotel by 20:00. As the streets emptied and the bars filled, La Rinconada became dangerous. In the meantime, however, the unmet needs of the city's residents complicated the work of scientists. Although Vergès and Hancco explained the aims of the study to the residents, the arrival of a group of predominantly white doctors and scientists still raised unrealistic expectations. "They have new devices that can stimulate the body," said one morning a man sitting at the entrance to the lab. "Do you think the doctors will look at me?" The older woman asked.

But the team did not have much to offer. So they were joined by eight medical students from the Punjab to help develop health questionnaires for about 800 people, including women and some children. Students measured people's blood pressure and provided health counseling - expanding Hancc's database. However, they could not treat anyone.

"It's an ethical problem we should have thought about earlier," Vergès said. "We don't just want to come here, collect data and disappear." He was afraid that conducting the study - and receiving help from the owner down - could be considered "justifying the exploitation of human beings ... But does that mean you don't do anything?" Or do you decide to carry out a study that could help these people? "

The miners stroll down the street in La Rinconada in the evening. It is estimated that 50 000 to 70 000 people live in the city.

Vergès hopes that the knowledge he gains will eventually lead to finding a treatment for CMS. Meanwhile, he also believes with Hancec that they will be able to persuade more Peruvian medical students to visit La Rinconada, and involve charities, such as Pharmacists Without Borders, that supply medicines to developing countries. Vergès also said that he hoped to persuade mine owners to take the health of workers more seriously than hitherto, as is the case in other regulated mines in Peru. "This study is the beginning of a long-term commitment for me," said Vergès.

Results of the study

In June, 5 months after leaving La Rinconada, Vergès' team presented some preliminary results of a study at the alpine physiology meeting in Chamonix. Miners from La Rinconada had huge amounts of hemoglobin in their blood, compared to 20 Peruvians living at sea level and another 20 Peruvians from 3800 meters above sea level. Some had more than 2 kilograms, the highest values ever recorded, says Vergès. (People living in the lowlands of Lima averaged 747 grams.) Contrary to his expectations - and what most CMS hypotheses predict - the weight of hemoglobin was not significantly higher in men with CMS than in those without CMS. .

However, one of the factors that correlated with CMS was blood viscosity: People with higher blood density suffered from the syndrome more often. Together, these two findings have led Vergès to speculate that in some people, the physical properties of their red blood cells reduce blood viscosity and the risk of CMS. Maybe their size or flexibility will improve cell flow, he said. It was an attempt at a follow-up study.

The team also reported pulmonary blood pressure, which in healthy people is about 15 millimeters of mercury (mmHg). In CMS patients, it increased to approximately 30 mmHg during rest and to 50 mmHg during exercise. "These are crazy values," says Vergès. "It's incredible that capillary tubes in the lungs can tolerate such pressure."

Electrocardiography has shown that such high pressure dramatically affects the heart: The right ventricle - which pumps blood into the lungs through the pulmonary artery - expands and its wall thickens. "The next question is how it has long-term effects on the heart," Vergès said. The team is still working through a range of other data, including genetics and epigenetics. However, Vergès is planning another trip to La Rinconada in February 2020.

Meanwhile, Sucasaire looked back at his participation in the mixed-feeling study. He appreciated the attention, but also hoped it would benefit his own health; but the data now being analyzed in France has not helped him yet. "The doctors were very kind, but I still have no results as to whether I am ill or anything," Sucasaire wrote in a WhatsApp report to Science this month. His knees, which the team did not investigate, still hurt him.

CREDIT: Tom Bouyer - Golden miners overlooking La Rinconada. The air here has only half the oxygen than at sea level, which poses a challenge to basic body functions.

Tip for a book from the Sueneé Universe

Arianna Huffington: Sleep Revolution - Transform your life night after night

The whole world has fallen into sleep crisisin which we are in the middle. Sleep deprivation affects our lives. Learn to improve your sleep, sleep all night to change your lives, ward off this crisis sleep revolution!

1

1