Pain rituals as a cure for a sore soul

06. 01. 2020

06. 01. 2020

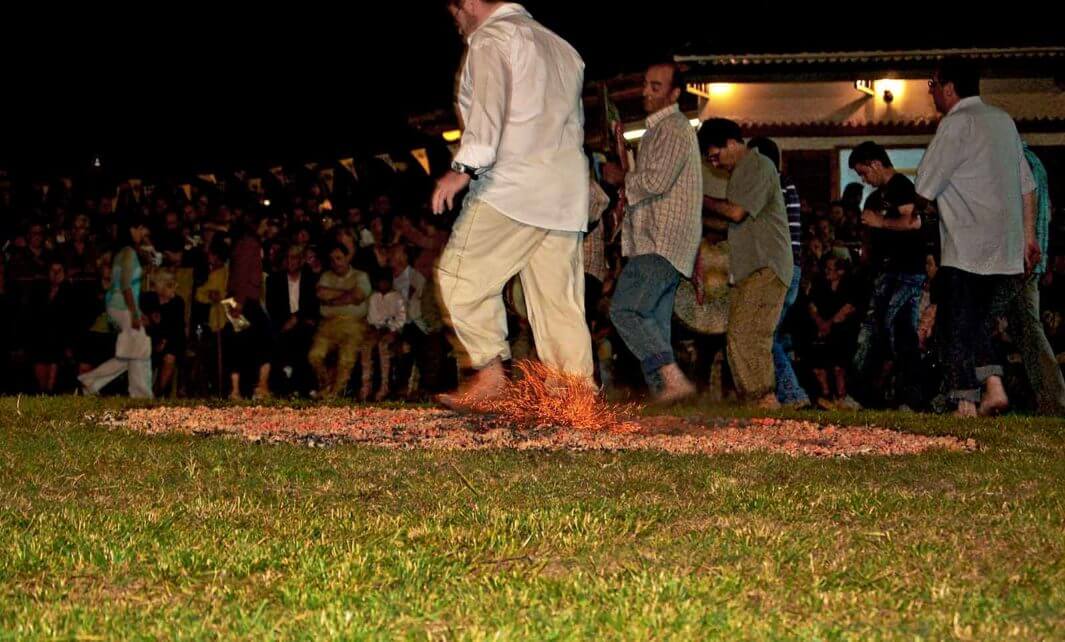

Physical pain helps from mental pain. Many people often resort to self-harm if they feel internal pain that can no longer be tolerated. This act is certainly not correct, but the effect is ultimately similar to the pain rituals. However, these have a longer-term and more complex impact. Imagine a group of forty men and women dancing and groaning, moaning and crying. Imagine barefoot dancing on a pile of hot coals.

Burn depression to dust

Dimitris Xygalatas is an anthropologist at the University of Connecticut. In 2005 he traveled to northern Greece to do his first fieldwork there. The Anastenaria Festival is organized in the village by a group of Orthodox Christians. The festival is described as tension, struggle and suffering. At the same time, it is synonymous with fulfillment and healing.

In his study, Dimitris portrays how an older woman described her healing through pain. She suffered from severe depression and could not even leave her house. It took years, eventually her husband arranged for membership and participation in Anastenaria. After a few days of dancing and walking on the hot coals, she began to feel better. And gradually her health began to improve overall.

Anastenaria is far from the only rite of pain. Despite huge risks, millions of people around the world perform similar rituals. Damage to the body is then immense - exhaustion, burns, scarring. In certain societies, these rituals are a kind of maturity or membership of the group. Non-participation can mean humiliation, social exclusion and worse fates. However, it is often voluntary participation.

Prescription Pain Cure

Although there is a risk of trauma, infection and persistent mutilation, these practices are prescribed as a medicine in certain cultures. For example, the Sun Dance ceremony is even worse than Anastenaria. This ceremony is practiced by various American tribes. It is considered a tremendous healing power. It involves penetrating or tearing meat…

Or at the Mexican ceremony of Santa Muerte, the participant must crawl in the clay on his hands and knees at great distances in order to ask the deity for fertility. In some parts of Africa, the so-called Zār is practiced. During the course, the participants dance until exhaustion to overcome depression or other mental distress.

Do these practices really help? Throughout history, many rituals have been carried out to raise the crop, summon rain or damage enemies. But these ceremonies have never been effective because they were more of a psychological nature, just as they had been blessed with soldiers before the battle. But anthropologists have long observed that rituals could have an impact on human relationships and pro-social behavior. Fortunately, these effects can now be studied and measured.

Dimitris began studying seriously in 2013 when he met Sammy Khan, a social psychologist at Keele University, England. Khan was the same question, therefore, what impact extreme rituals have on mental health, biased. This was followed by a long chat and a meeting with experts in the field. In the end, the couple managed to get a grant that gave them health monitoring equipment. A team of scientists was set up to monitor the effects of extreme ritual practices in the field. The results of their study were recently published in a magazine Current Anthropology.

Procession of suffering

Mauritius is a small tropical island in the Indian Ocean. Dimitris has been working in the field for the past ten years. It is a multicultural society of different ethnic groups who practice a wide range of different rituals following the colorful religion.

This diversity must be fascinating for any anthropologist, but what made Dimitris go to this island was the ritual practices of a local Tamil community. He was particularly impressed by a practice called kavadi attam (belly dance). Part of this ritual is a XNUMX-day festival, during which participants build large portable shrines (kavadi), which they wear on their shoulders in a several-hour procession to Lord Murugan's temple, the Hindu god of war.

But before they start building their loads, their bodies are crippled by sharp objects such as sharp needles and hooks. Some have only a few of these tongue or face piercings, others last even a few hundred throughout the body. Largest piercings have a broom handle thickness. They usually go through both faces. Some have hooks on their backs, with ropes attached to them, and these are important for pulling minivan-sized colorful cars.

With all these piercings and heavy loads on their shoulders, the participants of the ritual walk most of the day under the hot tropical sun until they reach the temple. The path is either over hot asphalt, where the participants are barefoot on the march, or even walk in boots made of vertical nails. When the participants of the ritual finally arrive at their destination, they still have to carry their heavy burden (45 kilograms) up to 242 steps to the temple.

Millions of Hindus around the world devote themselves to this tradition every year. The aim of the researchers was to investigate the effects of this suffering on mental and physical well-being without disturbing or affecting the rituals in any way. Over the course of two months, the experts used a number of measures to compare a group of ritual participants with a sample of the same community that does not practice the suffering ritual. The wearable medical monitor - a light bracelet the size of a classic watch - made it possible to measure stress levels, physical activity, body temperature and sleep quality. Demographic information, such as socioeconomic status, was collected during weekly home visits of ritual participants. The aim of the research was to create their own assessment of their health and well-being.

The patients suffered more pain

The analysis subsequently showed that people who suffered from chronic illness or social disability were involved in much more extreme forms of the ceremony - for example, the body was destroyed by a much larger number of piercings. And those who suffered the most pain were subsequently at their best.

A device that observed the health and well-being of the participants in the ritual marked a tremendous amount of stress. The electrodermal activity of martyrs (the amount of electrical conductivity in the skin that reflects changes in the autonomic nervous system and is a normal measure of stress) was much higher on the day of ritual compared to any other day.

A few days later, no negative effects of this suffering were observed physiologically on these martyrs. Quite the opposite - a few weeks later, there was a significant increase in the GP's subjective assessments about the well-being and quality of their lives compared to people who did not participate in the rituals. The more someone suffered pain and stress during the ritual, the more their mental health improved.

We perceive pain negatively

The results may be surprising for us, but no wonder. Modern society perceives pain negatively. Some rituals, such as the Kavadi ritual, pose a direct health risk. Piercings are subject to major bleeding and inflammation, and exposure to direct sunlight can cause intense burns, exhaustion beyond the carrying capacity and severe dehydration. Walking on hot asphalt can also cause numerous burns and other injuries. During the ritual, devotees face a great deal of distress and their physiology supports this.

But let's ask why some people are so excited about activities such as parachute jumping, climbing or other extreme sports that are not completely safe? For that huge euphoria of risking. And extreme rituals work essentially the same way. They release endogenous opioids in the body - natural chemicals produced by our bodies that provide a sense of euphoria.

Social link

Rituals are also important for socialization. If a marathon is to take place, people will meet and break up again. But participating in a religious ritual reminds people of their continued membership in the community. Members in these communities share the same interests, values and experiences. Their efforts, pain and exhaustion are affirmations and promises of continued commitment to the community. This increases their status towards the community by building a social support network.

Rituals are healthy. No, they certainly are not supposed to replace medical intervention or psychological help, and certainly not any amateur who can seriously hurt them. But in areas where medicine is less available and developed, in places where one would hardly find a psychologist, or do not even know what a psychologist is, these rituals are beneficial to both health and strength as well as to psychological well-being.

These ceremonial rituals have been passed down from generation to generation for many years and are still there. It means their importance for certain cultures and religious groups. They are sacred to them, and even if we do not understand it, it is necessary to tolerate and honor it.

6

6