1

1

Great pyramid in Cholla

17. 04. 2024

17. 04. 2024

1

1

17. 04. 2024

17. 04. 2024

6

6

16. 04. 2024

16. 04. 2024

8

8

15. 04. 2024

15. 04. 2024

1

1

27. 01. 2020

27. 01. 2020

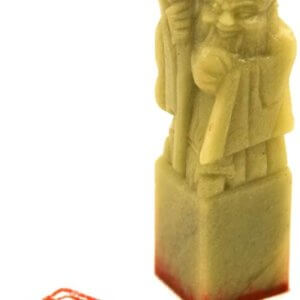

The Seal of the Legacy of the Empire, or also as the Seal of the First Emperor or the Chinese Imperial Seal, is a Chinese artifact that has been lost. Jade's seal was created by the first Chinese Emperor Qin Shi Huang. It was subsequently inherited by later Chinese emperors. Before the end of the first millennium AD, however, the empire disappeared from the historical records. It is said that the artifact has appeared in various places in Chinese history. However, the truth of these stories cannot be confirmed.

Although Chinese seals were most often associated with persons with authority, such as the emperor, princes, and ministers, they were also used by private individuals. The term for the use of the royal seal was xi (玺), while the other seals were known as yin (印).

Chinese imperial seal

Interestingly, during the time of Wu Ze Tian, who ruled as an imperial regnant between the late seventh and early eighth centuries AD, the seal became known as bao (宝), which literally means treasure. This was probably due to the fact that Wu Ze Tian did not like the word xi, which sounded similar to si (死), which means to die. The seal owned by private individuals was known as yin yang (印章), yin jian (印鑑) or tu zhang (圖章). Unlike the office seals, these personal seals were engraved with names that served as the person's signature.

Chinese seals were made of different materials. They were resistant to stone or jade and less resistant to bamboo or wood. Needless to say, the seals were made in all shapes and sizes and were an expression of craft creativity. Sometimes they were simple blocks, while others were carved by mythical creatures. Some of the seals on their sides contained engravings that effectively combined several seals into a single object.

Even the engravings of seals are fascinating for self-study. In addition to using different scripts, various phrases were engraved on the seals. Seals with the person's name were probably the most common, although there were differences. For example, there were seals indicating the personal name, the style (or courtesy) of the name, the combination of the personal name and the place from which it originated, etc.

Another category of seals was the study seals, which bear the name of a personal private study. Examples of studio seals include poetry seals on which a poem or proverb has been engraved, lalias seals and storage seals that have been applied to books or images kept by the user. So it is not unusual for a person in ancient China to have multiple seals.

Sealing was done with black ink, an important part of which was crushed vermilion. There were two ways to turn the powder into ink. The first option was to mix cinnabar with castor oil and silk springs, the second was to mix castor oil with moxa (dried wormwood).

The ink from the first type of production was very dense as silk strands bonded the mixture together. The ink was also very greasy and in red. On the other hand, the ink according to the second recipe was loose, non-greasy and had a darker red color. The plant ink dries faster than the silk-based ink, as the plant extract binds as effectively to oil as to silk. For the same reason, however, he easily smeared.

Depending on how the signature of the seal looked, the seal fell into one of three categories. The first was zhu wen (朱 文), which literally means red markings (sometimes referred to as yang seals). The imprint of this seal was red with a white background. The second category was bai wen (白文), which means white characters. The seal was the opposite of the first category - the white seal on a red background. The third category was called as zhu bai wen xiang jian yin (朱白文 相間 印), which means the red and white markings of the combined seal. It was basically a combination of zhu wen and bai wen seals.

Seals were used as early as the 11th century BC during the Shang Dynasty or the subsequent Zhou Dynasty. Initially, there were records of seals from the Zhou Dynasty, but some experts in the field argued that the seals were already used in the Shang Dynasty and the evidence was to be the bronze vessel that was made during this period. It was decorated with various patterns.

The presence of such features could mean that the seals were also used to decorate clay containers. From the archaeological point of view, the oldest known seals come from the 5th century BC. During this period the seals were made mainly of copper, but also of stones, bronze and even silver.

The period of warfare in China ended in 221 BC. King Qin conquered six more warring states, which united China. Qin became the first Chinese emperor and was later known as Qin Shi Hauang. And so began the story of the imperial seal - the heirloom seal of the empire he had made.

This artifact is known as Chuan Guo Yu Xi (传 国 玉 玺), which in literal translation means Yad (sign for jade and jade) seal passed through the empire. It follows that the seal was made of jade, which was a very important and symbolic material in the country.

Jade has been used in China since the Neolithic (seventh to fifth millennium BC). It was used to make sacrificial vessels, ornaments and even musical instruments. Needless to say, this material was valued for its great aesthetic value. The ancient Chinese even believed, but erroneously, that jade was able to protect the body from decay after death. They put so much weight on him.

That is why some Chinese elites were found in jade suits, especially skeletal remains from the Han Dynasty. Jade was also surrounded by symbolic meanings. For the Chinese, it represented beauty, purity and charm. He was even supposed to represent eleven virtues - indulgence, justice, decency, truth, credibility, music, loyalty, heaven, earth, morality and intelligence.

And what happened to the royal seal, you read in the second part.