1

1

Arkaim and the texts of Rgveda about his builders

25. 04. 2024

25. 04. 2024

16. 09. 2016

16. 09. 2016

There are amazing buildings on the map of the old world, which are extremely complex in their structure. The Egyptians and Mayans had their temples. Hindus built complicated temples all over Asia. The Greeks created the Parthenon, the Babylonians the Temple of Jupiter and the mythically hung gardens. The Romans left behind the construction of roads, temples, viaducts and the Colosseum. Roman sculptors mastered working with chisels and marble or alabaster and breathed physical beauty into them.

With the exception of artifacts such as the Antikythera mechanism, an astronomical computer found by fishermen on the seabed near the island of Antikythera in 1901, the development of technology in the ancient world seems clear and understandable to us.

Going even further back in time, we come to the question of how Egyptian civilization could prosper for 3000 years without improving the tools used in breaking and shaping the stone. Since 1984, when Analog magazine published my article Advanced Engineering in Ancient Egypt, there has been a contradiction between the subject. In the article, I assumed that the ancient Egyptians used more advanced technologies than originally thought and used advanced tools and methods for cutting granite, diorite and other difficult-to-machine materials. It does not seem likely to me that architects and craftsmen have used stone tools and copper chisels for three millennia.

Going even further back in time, we come to the question of how Egyptian civilization could prosper for 3000 years without improving the tools used in breaking and shaping the stone. Since 1984, when Analog magazine published my article Advanced Engineering in Ancient Egypt, there has been a contradiction between the subject. In the article, I assumed that the ancient Egyptians used more advanced technologies than originally thought and used advanced tools and methods for cutting granite, diorite and other difficult-to-machine materials. It does not seem likely to me that architects and craftsmen have used stone tools and copper chisels for three millennia.

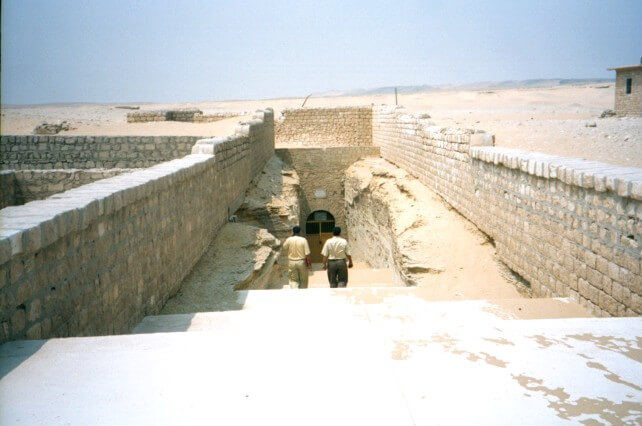

The most interesting and convincing evidence to theorize how difficult it was to work with stone in ancient times are the incredible granite and basalt boxes in the Serapea rock tunnel in Saqqara. In these mysterious tunnels, which have been carved out of the limestone subsoil, there are over 20 huge granite boxes. These 70-ton boxes with 20-ton ages were mined in Aswan, more than 500 miles away, and housed in vaulted crypts embedded in the walls of the labyrinth of underground passages. All boxes were finished on the inside and on the bottom of the lid, but not all were finished on the outside. It seems that the work in Serapeo was suddenly interrupted, because there were boxes in several stages of completion - boxes with lids, boxes on which lids had not yet been placed, as well as a roughly machined box and a lid at the entrance. The floor of each crypt was a few feet lower than the floor of the tunnel. An iron railing was installed to prevent visitors from falling.

In 1995, I examined the inner and outer surfaces of the two boxes in Serape using the 6-inch ruler with 0,0002 finger accuracy.

In one of the crypts is a granite box with a broken corner, and this box is accessible by stairs down the lower floor. The outside of the box looks unfinished, but a flash of high gloss on the inside forced me to enter. I ran my hand over the granite surface and it reminded me of how I had walked a thousand times over my hand on the same surface when I worked as a machinist and later as a press and toolmaker. The feeling of the stone was exactly the same, although I wasn't sure of its exact softness. To verify the impression, I placed a ruler on the surface and found that the surface was absolutely flat. There was no light between the ruler and the stone. It would shine if the surface is concave. If the surface were convex, the ruler would swing back and forth. To put it mildly, I was amazed. I did not expect such precision, because it would certainly not be necessary for the sarcophagus of a bull, another animal or a human.

I slid the ruler over the surface - horizontally and vertically. He was without deviation, really straight. It was similar to precision ground boards used in manufacturing to verify the accuracy of parts, tools, gauges, and a myriad of other products that require extremely precise surfaces and dimensions. Those familiar with such products and the relationship between gauges and slabs know that a gauge can show that the stone is flat within the tolerance of the gauge - in this case 0,0002 inch (0,00508 mm). If the gauge moves 6 inches along the surface of the stone and the same conditions are found, it cannot be said with certainty that the stone is within the same tolerance above 12 inches. The stone must be examined by other means.

However, exploring the granite surface with a ruler gave me enough information to conclude that I needed a longer ruler and even more sophisticated adjusting devices to determine the accuracy of the inner surface of the box. It also made me feel that every corner of the box had a slight rounding, which continued from the top of the box to the bottom of the box, where it collided with the rounded corner of the box floor.

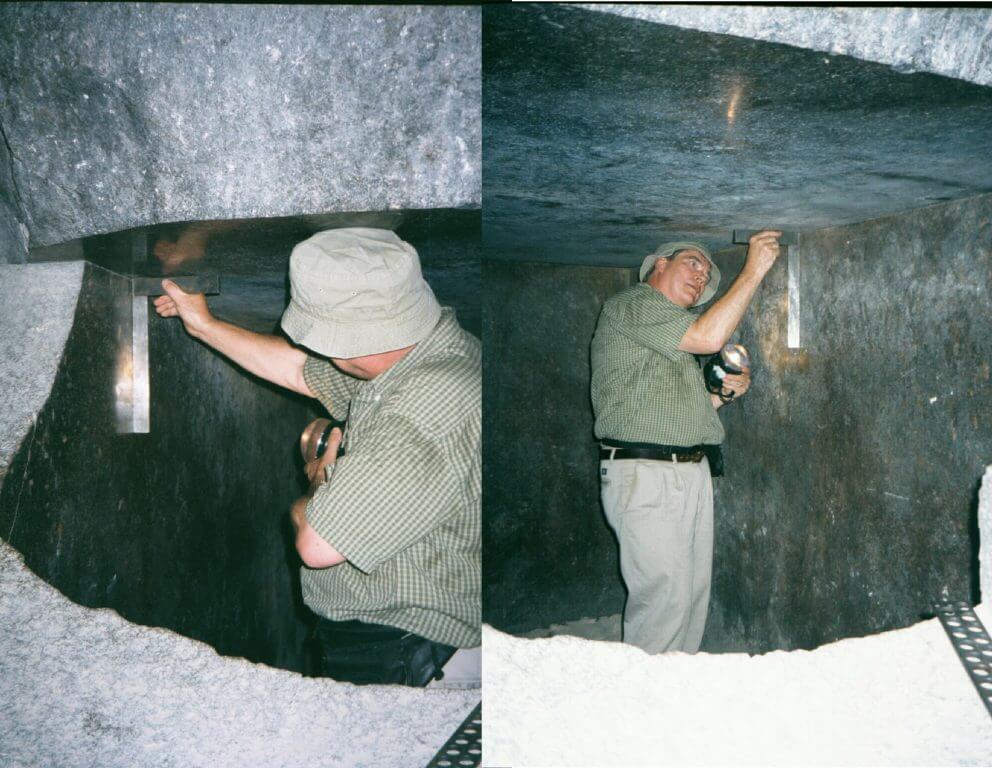

The artifacts I measured in Egypt are made very precisely using remarkable production methods. They are incredibly accurate, but the origin or intention of their origin will always be the target of speculation. The following series of photographs comes from Serape on August 27, 2001. The ones I'm inside inside one of these huge boxes show how I examine the perpendicularity between the 27 tonne age and the inner surface on which it is placed. The ruler I used had an accuracy of 0,00005 inch.

I have found that the underside of the lid and the inner wall of the box have a square shape and also that the walls are not perpendicular to only one side of the box but on both. This increases the level of difficulty in performing such performance.

I have found that the underside of the lid and the inner wall of the box have a square shape and also that the walls are not perpendicular to only one side of the box but on both. This increases the level of difficulty in performing such performance.

Let's take it from the point of view of geometry. In order for the lid to be perpendicular to both inner walls, the inner walls would have to be parallel to each other along the vertical axis. In addition, the top of the box should form a plane that is perpendicular to the sides. This makes elaborating the interior much more difficult. The manufacturers of these boxes in Serape not only created inside them surfaces that were straight vertically and horizontally, but also parallel to each other and perpendicular to the top with sides of 5 and 10 feet. But without such parallelism and squareness of the upper surface, squareness on both sides would not exist.

Straight areas on the inside of the boxes showed a high degree of precision comparable to that of modern production facilities.

Finding such accuracy in any epoch in human history leads us to the conclusion that there must have been a sophisticated system of accurate measurement at the time. This is an area of intense interest for technicians like me who find a similar language here in Egypt. This is the language of science, technology and production. Our ancestors in this ancient country posed a challenging challenge to future generations of scientists, engineers, architects and those who shape materials at their direction. The challenge is to recognize what they have created and to provide sensible, evidence-based answers that will give ancient builders credit for what they have achieved.

The ancient Egyptians, who built pyramids and temples and created monumental stone sculptures, thought like architects, engineers and craftsmen. Were the ancient archaeologists responsible for the legacy they left us? Are modern interpretations of the amazing performances of the ancient Egyptians irrelevant in providing new information about this ancient culture? Are the thoughts and conclusions of Western writers and travelers standing in front of the Great Pyramid a hundred years ago (or 4500 years after it was built) more intrinsically linked to the ancient Egyptian mind than those of those who came centuries later? What can be described as a modern perspective? In his time, Herodotus would certainly be considered modern. Petrie, Marriette, Champollion and Howard Carter also thought modern, but at the same time their thinking was influenced by the prejudices and stereotypes of the time.

As far as the full knowledge of the technological skills of the ancient Egyptians is concerned, we cannot draw any definitive conclusion. What we have left is only a skeleton of what existed in the time of ancient Egypt. This skeleton is preserved in the form of a precisely worked stone. I am convinced that the dress in which we put the skeleton is just ordinary rags compared to what it should be worn. In the past, I suggested that the ancient Egyptians could use more advanced technology to build the pyramids. At the same time, I expressed doubts about the construction methods preferred by Egyptian scientists. These methods are primitive and include stone and wood sticks, copper chisels, drills and saws as well as stone hammers for working igneous rocks.

When we look at the incredible accuracy of the Serape boxes, we should recall the work of Sir William Flinders Petrie, who measured the Pyramid in Giza. Meraniami found that the tiles were cut to the accuracy of the 0,010 thumb and that part of the descending corridor had an 0,020 inch accuracy at the length of 150 tracks.

To understand how the ancient Egyptians created their work, we must rely on the research of scientists and engineers. They perform measurements using modern instruments, analyze the full range of work and compare it with our own capabilities. However, Egyptian scientists cannot explain how the ancient Egyptians created their monuments. For example, pulling a 25-ton block from granite over wooden rollers with great difficulty was possible, but it does not explain how they could move a 500-ton obelisk or monolithic statues weighing 1000 tons. The carving of a few cubic centimeters of granite with dolerite does not explain how thousands of tons of extremely precise granite could have been extracted from the subsoil and placed in the form of monumental works of art in the temples of Upper Egypt. If we want to know the real abilities of the ancient Egyptians, we should know and appreciate the full scope of their work.

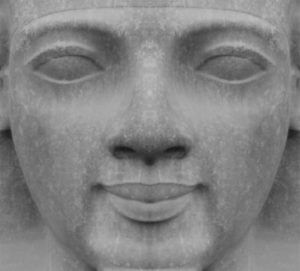

The boxes in Serape are a challenge for those who are trying to explain the skill of the ancient Egyptians, they are not intricate surfaces like the statues of Ramses II that adorn the North and South temples. You may be wondering why I turned my attention to the statues. Because the monolithic statues of Ramzes are a challenge for anyone who would try to explain how they were made.

What does Ramzes' face have to do with a modern precision-made object such as a car? They are smooth contours with clear features and perfect symmetry. One side of Ramzes' face is an ideal mirror image of the other side and means that it was made with accurate measurements. So they carved the statue into intricate details. The jaw, eyes, nose and mouth are symmetrical and were created using a geometric system that includes a Pythagorean triangle as well as a golden rectangle and a golden triangle. Ancient sacred geometry is encoded in granite.

While doing research for my book The Giza Power Plant, I first met Ramzes the Great. It was at a museum in Memphis in 1986 and I was mainly interested in construction and pyramids, so I was not interested in statues or visiting temples in the south. Looking down the entire length of the 300-ton Ramzes statue, I noticed that the nose was symmetrically shaped and the nostrils were the same. The significance of this fact became more important when I visited the temples in 2004 and was fascinated by the three-dimensional perfection of the statues of Ramzes in Luxor. I took digital pictures so I could explore some of the features of the sculptures on my computer. The images revealed a much higher level of technology than I mentioned above.

While doing research for my book The Giza Power Plant, I first met Ramzes the Great. It was at a museum in Memphis in 1986 and I was mainly interested in construction and pyramids, so I was not interested in statues or visiting temples in the south. Looking down the entire length of the 300-ton Ramzes statue, I noticed that the nose was symmetrically shaped and the nostrils were the same. The significance of this fact became more important when I visited the temples in 2004 and was fascinated by the three-dimensional perfection of the statues of Ramzes in Luxor. I took digital pictures so I could explore some of the features of the sculptures on my computer. The images revealed a much higher level of technology than I mentioned above.

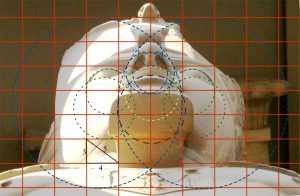

When photographing Ramzes, it was important that the camera be oriented along the center axis of the head. In order to be able to compare one side of the face with the other, I made the image inverted horizontally and 50% transparent. Then I placed the inverted image over the original image to compare the two sides. The results were remarkable. I discovered the elegance and precision that is common in Lexus under the conditions of production technology that exists today. The techniques that the ancient Egyptians allegedly used - as they taught us at school - will not bring the accuracy of the Ford T model, let alone Lexus or Porsche.

We know that the ancient Egyptians used a grid in their designs and that such a method or technique is intuitive. There is no need for a quantum leap from the artisan's imagination to the modern way of construction. In fact, this technique is used today not only in design, but also in organizational procedures and concepts. Graphs and tables are used to convey information and organize work.

We know that the ancient Egyptians used a grid in their designs and that such a method or technique is intuitive. There is no need for a quantum leap from the artisan's imagination to the modern way of construction. In fact, this technique is used today not only in design, but also in organizational procedures and concepts. Graphs and tables are used to convey information and organize work.

With this in mind, I took a photo of Ramzes and placed a grid on it. Of course, my first task was to determine the size and number of cells used in the grid. I assumed that facial features would lead me to an answer, and I studied which qualities would be most appropriate. After much deliberation, I used a grid according to the size of my mouth. It seemed to me that the mouth had something to tell us due to its unnaturally inverted shape, so I placed a grid with cell dimensions that were the same height and half the width of the mouth. It was then easy to create circles based on the geometry of the facial features. However, I did not expect them to match the lines in so many places. In fact, I was outraged by this discovery. My mind flashed, "Okay, now it's no longer a coincidence and is it a reflection of the truth?"

Thanks to the grid, I found that Ramzes' mouths had the same proportions as a classic right triangle with a 3: 4: 5 aspect ratio. The hypothesis that the ancient Egyptians knew about Pythagoras' triangle before Pythagoras and could even teach Pythagoras their ideas has already been discussed among scientists. Ramses 'face was carved on the basis of Pythagoras' triangle, whether it was the intention of the ancient Egyptians or not. As we can see in Figure 5, the Pythagorean grid allows us to analyze the face like never before.

The geometry and accuracy of the Ramzes statues, as well as the discovery of traces of instruments on some of the statues, are described in more detail in the book Lost Technologies of Ancient Egypt. Small, seemingly insignificant mistakes caused by old tools bring to light information from which we can derive the method of production.

Another notable example of granite working is found on a hill 5 miles from Giza. Abu Rawash was recently discovered as the "lost pyramid" by Záhí Hawáss, Secretary General of the Supreme Council for Monuments in Egypt. I didn't have high expectations when I first visited this place in February 2006. Well, what I found was a piece of granite so remarkable that I returned to this site 3 more times to show witnesses of its unique properties. I have been accompanied on various occasions by David Childress, Judd Peck, Edward Malkowski, Dr. Arlan Andrews and Dr. Randall Ashton. Edward Malkowski immediately called the stone the new pink-red Rosette plaque. Mechanical engineer Arlan Andrews came to the same conclusion independently.

A closer look at the surface of the block in Figure 6-F shows strips that are approximately 0,030 inches (0,762 millimeters) and 0,06 inches (1,52 mm) apart. This is a common feature of many artifacts found in Egypt, including some holes and cores from these holes. The rounding where the cutting surface ends is a mystery when we consider the different ways in which a block could have been created. One of the proposed explanations was that the stone was machined with a jigsaw, which was curved, thus creating curves on the stone face. If it were possible, this could explain one rounding of the block. But whether you look at the block from above or from the side, you will always see a curvature. Taking all this into account, we must completely eliminate the straight saw. Another possibility that was suggested to me was that the stone was cut with a stone ball coming from the pivot point. But it is obvious that the stone is machined with much greater precision.

I tried to imagine a process in which the whole piece would be cut in one step, but I could not come up with a method that would not require the tool more than its possibilities. In other words, suppose a larger block was cut with an saw at an angle along the grooves. Depending on the thickness of the whole block, a thin block would be separated from a thicker one. But placing the stone on the saw at a certain angle would result in an increase in the cutting area. In order to find the answer to this puzzle, it was necessary to calculate the radius of the saw. The stone was cut with a circular saw that was more than 37 feet in diameter. This seems almost unbelievable, but the evidence is carved in stone for anyone who wants to measure it and shown in Figures 7 and 8.

The boxes in Serape, the statue of Ramses and the stone in Abu Rawash are three examples of many that have been examined in detail and are mentioned in the book Lost Technologies of Ancient Egypt. Other unique artifacts such as the columned hall in the Temple of Dender, the worked stones of Giza, the unfinished obelisk, the famous Petrie's core, the unique artifact that has been the source of controversy since Petrie discovered it, and the White Crown of Upper Egypt are a remarkable example of ancient Egyptian geometry. Ellipsoids and ellipses were an integral part of the knowledge of the ancient Egyptians. The evidence is carved into hard granite and speaks of the amazing abilities of the ancient nations.